"It's going to be OK".

A frequent factor in accidents is that conditions actually encountered are very different to those anticipated, particularly worse weather. Both crew members may have shared the same overly optimistic "mental model" and have difficulty switching from trying to resolve short term problems to seeing that the big picture is unsatisfactory - in other words, they become preoccupied with "struggling with the alligators, when the objective was to drain the swamp".

A related influence is "plan continuation bias", or in ordinary language "get-there-itis". In essence, this means that having started out with one idea in mind (e.g. "we have thought it through and we'll be able to land"), it is difficult to recognise that changed circumstances have actually undermined that plan's validity. Humans have a natural tendency both to look for and accept information which confirms what they already believe, and also to reject any that contradicts it.

An extreme example of "plan continuation bias" may have resulted in the destruction of a brand-new B737 (total flight time 143 hours) in 2013, after a "traditional" non-precision approach. The weather information on which the crew had based their plan was "10km, nil weather, few CB, sct 1700ft." But in fact, there was a significant thunderstorm shower on short final with very degraded visibility in heavy rain.

Having given his F/O the sector (i.e. takeoff and landing) the Captain was Pilot Monitoring. At 900 ft a single light was seen through haze and rain but not more. At DA (465 ft), the Captain had acquired some visual reference, but the PF did not, and a missed approach should then have been initiated. Instead, the PM Captain instructed the PF to continue descending. The PF said he still had no visual reference, but disconnected the autopilot, and the aircraft descended further, into heavy rain. Neither pilot now had adequate visual or adequate instrument reference.

Having given his F/O the sector (i.e. takeoff and landing) the Captain was Pilot Monitoring. At 900 ft a single light was seen through haze and rain but not more. At DA (465 ft), the Captain had acquired some visual reference, but the PF did not, and a missed approach should then have been initiated. Instead, the PM Captain instructed the PF to continue descending. The PF said he still had no visual reference, but disconnected the autopilot, and the aircraft descended further, into heavy rain. Neither pilot now had adequate visual or adequate instrument reference.

At 150ft the Captain took over control, but instead of going around, he continued descending "expecting to see the runway after passing through the rain". At 20ft RA he finally called go-around - but by then it was far too late and the aircraft struck the water and was destroyed, fortunately without loss of life.

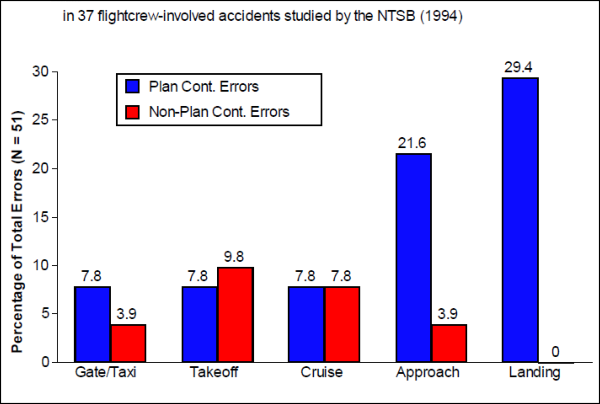

The work by Judith Orasanu just referred to showed the prevalence of such "plan continuation errors" in much earlier approach and landing accidents, and although no similar detailed analysis of more recent accidents has been found it is not unreasonable to assume that the patterns remains broadly similar in many accidents since.

A "fail-dangerous" mental plan.

Unfortunately, the basic plan or mental model used in most airline operations is not "fail-safe". The almost universal basic plan is to "fly an approach and make a visual landing, unless a G/A is needed". Of course, this works 99.99% of the time. But from an air safety viewpoint, the "unless" is the weak point in the chain, as "keep going to make a visual landing" is the default plan. "Plan continuation", or any other failure to adhere to the criteria for "unless a go-around is needed" can only make the situation hazardous.

IATA's 2013 safety report showed its concern that far too many hazardous and unstable approaches are continued to a landing, and pointed to the need for operators to emphasise to their pilots that a go-around was preferable in these circumstances, even if it did have an adverse commercial effect.

The normal "mental model" for air transport approaches needs to be reversed and become "fly an approach and go-around, unless a visual landing can be made". The plan is then "fail-safe", as it is biased towards a go-around. Even though the fail-safe is needed on only a minute proportion of actual occasions, in principle this precaution is no different to that taken prior to every takeoff, when the crew brief on the actions for an even more improbable event. A total loss of thrust just prior to V1 something almost no pilot will ever experience in real life, but for which it is vital to deal with correctly IF it does. The detailed actions for this are rehearsed every day.

Go-around loss of control.

The nature of modern automated aircraft makes this particularly important since an unexpected go-around can result in serious confusion about the aircraft state. Instinctive physical inputs by the pilot flying to thrust and pitch controls can be over-ridden by correctly functioning but unexpected automated modes. These may be readily understandable from the Flight Mode Annunciators, but particularly when the PF is startled into commencing the Go-Around, he or she may become confused and overwhelmed by other physical phenomena such as accelerations, pitch changes and noise.

Reflex actions and lags in response can lead to conflicting inputs between automation and pilot resulting in near or total loss of control, and the August 2013 study of 14 such events by the French Accident Investigation Authority makes sobering reading. The approach plan must include full preparation for a safe go-around on 100% of approaches, and this extremely difficult to achieve if the pilot flying is focused on landing.

Examples of "startle factor" combining with "plan continuation bias" include a serious incident and damage to an A380 in 2010. The F/O as PF flew an unstable visual approach, terminated by the Captain as PM calling for a Go-around 1 mile from the threshold with the aircraft still at 480 feet and 210 kts.

Although the Captain's monitoring had been effective in the sense that the approach was terminated rather than resulting in a runway overrun or worse, the PF was so unprepared to go-around that the aircraft shot through the unusually low initial go-around altitude of only 1000ft, and reached over 300kts at low altitude in highly congested airspace, damaging the flaps in the process.

When a PicMA is in use, deterioration in the weather, or most other external changes, are of no basic significance to the P2 who is PF: his mental model remains "I am going to keep flying on instruments whatever the weather. I'm ready to fly a go-around any time one is called for".