Misusing data.

One particular measurement used by Hofstede - "power-distance index" (PDI), basically natural deference to authority - has been given significant exposure outside the aviation community, and may influence researchers and non-operational airline managers as well as pilots. In a classic example of "a little knowledge is a dangerous thing", a writer named Malcolm Gladwell achieved considerable publicity in 2008 for a book entitled "Outliers", in which he addressed this issue, developing what he called "The ethnic theory of plane crashes".

Gladwell uses Hofstede's and Merritt's work to claim that "The single most important variable in determining whether a plane crashes is not the plane, it is the [national] culture the pilot comes from." In fact (as on other subjects) he manages to confuse correlation with cause, and after quite correctly identifying many aspects of the problem, his own cultural biases cause him to reach a fundamentally flawed conclusion.

Unfortunately, Gladwell's prominence as a popular writer means this misleading interpretation has been has been given huge public exposure, and if anything has almost certainly harmed the industry's ability to implement a better solution.

Gla

dwell uses two particular accidents to support his "ethnic theory", which basically amounts to "you have be like Americans to fly airliners safely". These are the 1990 Avianca New York fuel exhaustion accident, and the 1997 Korean Airlines Guam CFIT accident. These are particularly useful studies as they involved foreign carriers on US territory so were very thoroughly investigated by the NTSB.

In both accidents the NTSB's found that the Captain's overall management of the flight was defective, with inadequate teamwork, leading to recommendations about CRM training.

According to the "ethnic theory", the probability of this kind of accident is directly connected with PDI, which is much stronger in some cultures than others: therefore "being a good pilot and coming from a high power-distance culture is a difficult mix". The entire problem can only be fixed if pilots from "high PDI" cultures are made more like those of low PDI cultures such as the USA. However this is a grotesque over-simplification which ignores many other factors, as we have seen.

The Guam accident caused a significant focus on "cultural" issues, because it involved Korean culture, which indeed does have a high power-distance index. It's inescapable that the crew were affected by this, as has been the case in many other accidents involving pilots from high PDI cultures. If this is seen only as a "cultural" problem, the obvious solution is therefore CRM training to reduce the PDI culture on the flight decks of otherwise high PDI pilots.

Gladwell even made the absurd implication that a completely flat CCAG is actually an assumption of modern aircraft design, saying in one interview that "Boeing and Airbus design modern, complex airplanes to be flown by two equals".

In fact of course they design aircraft for two pilots, PERIOD. Every country requires that one of these pilots must be designated as pilot in command, with very significant authority over the other by law, and that requires the two pilots cannot be equals.

Identical culture - radically different results.

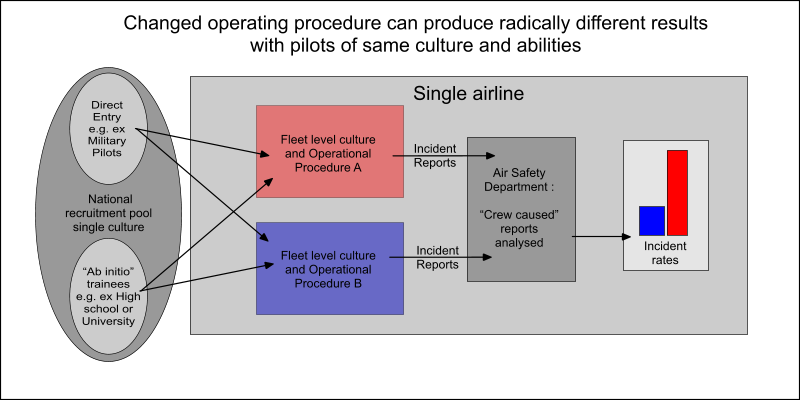

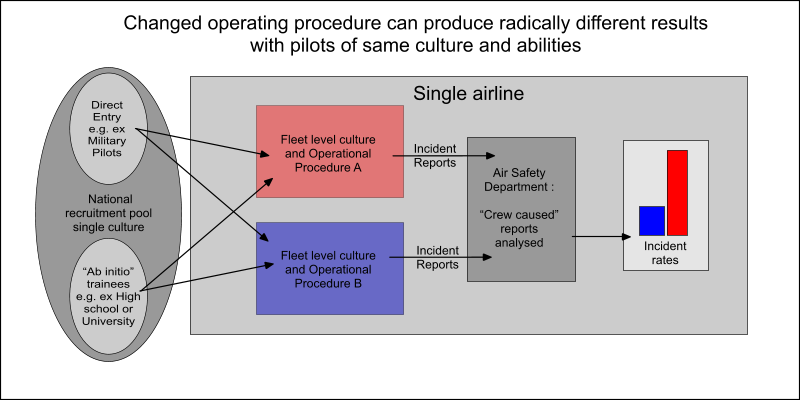

In fact this emphasis on "culture" at the national level as the primary reason for ineffective monitoring is very misleading. Suppose that dramatically different safety results were found in operations by pilots with the same societal cultures, from identical educational and other backgrounds and subject to identical training and regulatory criteria. This might lead to some curiosity as to what was different between the two groups. In fact this situation has arisen, and is described in more detail in "where's the data" under "an inadvertent experiment", but is summarised here.

An airline kept safety records for separate operational divisions over a number of years. These divisions, here referred to as "A" and "B" drew from common pilot sources, but had quite different internal (fleet level) cultures. "A" used traditional PF/PNF procedures and "B" used a "delegated flying" philosophy including PicMA.

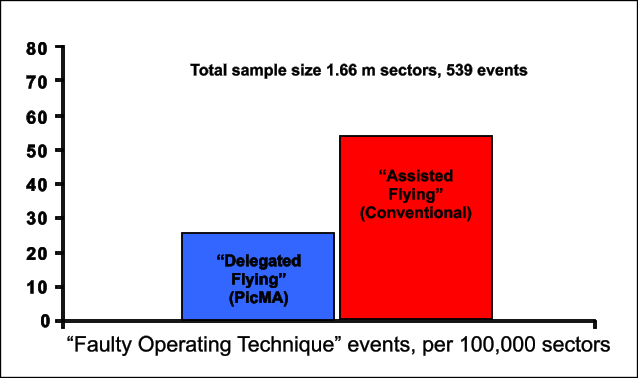

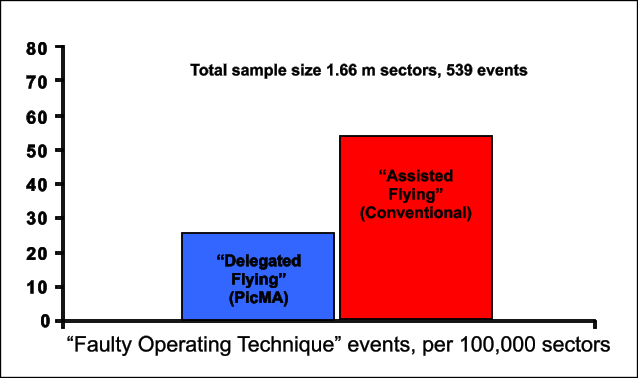

The airline kept detailed records of safety events, and classified those arising from crew errors as "faulty operating technique". Although not a rigorously controlled experiment, the statistical data from this experience gives reason to believe that the fleet culture and operational philosophy could have a very significant impact on safety. The following diagram illustrates the different rates of occurence of "crew error" incidents in two parts of the same airline.

The airline kept detailed records of safety events, and classified those arising from crew errors as "faulty operating technique". Although not a rigorously controlled experiment, the statistical data from this experience gives reason to believe that the fleet culture and operational philosophy could have a very significant impact on safety. The following diagram illustrates the different rates of occurence of "crew error" incidents in two parts of the same airline.

This graph covers some 1.66 million sectors, during which 539 incidents occured that were attributed to the crew's "faulty operating technique".

This graph covers some 1.66 million sectors, during which 539 incidents occured that were attributed to the crew's "faulty operating technique".

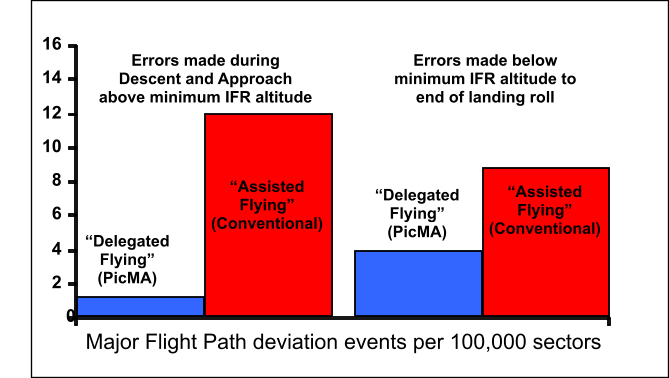

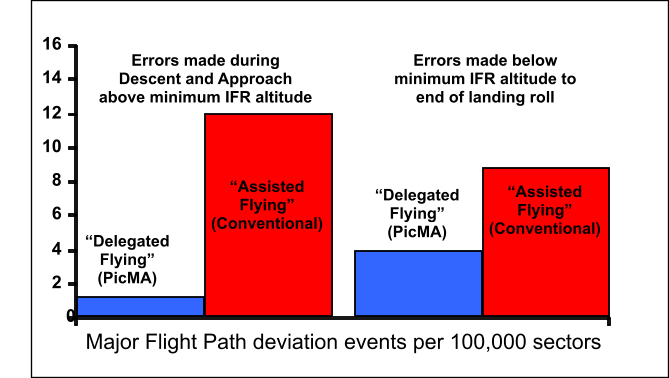

A different analysis of approach and landing events during an earlier period produced the result shown below.

(The records used here pre-date awareness of Hofstede's "dimensions" but (in this author's opinion) if tested at the time, "A" would probably have scored higher on individuality and "B" on uncertainty avoidance. Both "A" and "B" pilots would have had a high PDI, but for different reasons: "A" placed a lot of emphasis on the Captain' status (e.g. Captains routinely stayed in a higher quality hotel to the other crew members); while "B" had a steep authority gradient induced by rank, with a large number of very young and low experience co-pilots flying with very high experience Captains.)

(The records used here pre-date awareness of Hofstede's "dimensions" but (in this author's opinion) if tested at the time, "A" would probably have scored higher on individuality and "B" on uncertainty avoidance. Both "A" and "B" pilots would have had a high PDI, but for different reasons: "A" placed a lot of emphasis on the Captain' status (e.g. Captains routinely stayed in a higher quality hotel to the other crew members); while "B" had a steep authority gradient induced by rank, with a large number of very young and low experience co-pilots flying with very high experience Captains.)

The biggest difference however was probably that "B" operated a delegated flying SOP to the greatest possible extent, with the co-pilot taking over as PF during the climb, and virtually all approaches being conducted using PicMA, while "A" operated with standard PF/PNF duties. So group "B" operated with a reversed authority gradient to "A" for the majority of the time, and experienced significantly lower crew-caused incident rates. This was not due to superior flying skills or any attempt to change the performance and behaviour of individual pilots, but arguably, simply the difference in operating procedures.

The airline kept detailed records of safety events, and classified those arising from crew errors as "faulty operating technique". Although not a rigorously controlled experiment, the statistical data from this experience gives reason to believe that the fleet culture and operational philosophy could have a very significant impact on safety. The following diagram illustrates the different rates of occurence of "crew error" incidents in two parts of the same airline.

The airline kept detailed records of safety events, and classified those arising from crew errors as "faulty operating technique". Although not a rigorously controlled experiment, the statistical data from this experience gives reason to believe that the fleet culture and operational philosophy could have a very significant impact on safety. The following diagram illustrates the different rates of occurence of "crew error" incidents in two parts of the same airline. This graph covers some 1.66 million sectors, during which 539 incidents occured that were attributed to the crew's "faulty operating technique".

This graph covers some 1.66 million sectors, during which 539 incidents occured that were attributed to the crew's "faulty operating technique".  (The records used here pre-date awareness of Hofstede's "dimensions" but (in this author's opinion) if tested at the time, "A" would probably have scored higher on individuality and "B" on uncertainty avoidance. Both "A" and "B" pilots would have had a high PDI, but for different reasons: "A" placed a lot of emphasis on the Captain' status (e.g. Captains routinely stayed in a higher quality hotel to the other crew members); while "B" had a steep authority gradient induced by rank, with a large number of very young and low experience co-pilots flying with very high experience Captains.)

(The records used here pre-date awareness of Hofstede's "dimensions" but (in this author's opinion) if tested at the time, "A" would probably have scored higher on individuality and "B" on uncertainty avoidance. Both "A" and "B" pilots would have had a high PDI, but for different reasons: "A" placed a lot of emphasis on the Captain' status (e.g. Captains routinely stayed in a higher quality hotel to the other crew members); while "B" had a steep authority gradient induced by rank, with a large number of very young and low experience co-pilots flying with very high experience Captains.)