Easy errors to make, but hard to correct.

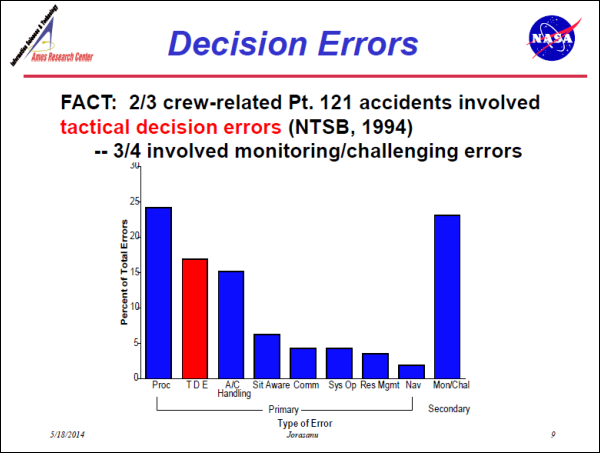

Such a sequence of events typically involves "tactical errors" and/or "errors of omission". These are known to be particularly difficult for junior crew-members such as First Officers to monitor and correct effectively, when they are made by the Captain. The following chart from a paper by Judith Orasanu for NASA confirms that such errors are major contributors to accidents, and that most such accidents involved a "primary" error such as a tactical decision error, followed by a monitoring/challenging failure. We also know that in the vast majority of cases, the PM was the First Officer.

A typical scenario might involve the Captain, as the PF and aircraft commander, being confident that all will be well. Both Captain and First Officer are competent, well trained and experienced; it seems like it's a beautiful night and they can handle any minor problems that might arise during the descent and approach. The Captain sees no need to go through all the formalities of the laid-down procedures for briefing for a full IFR approach and go-around.

A typical scenario might involve the Captain, as the PF and aircraft commander, being confident that all will be well. Both Captain and First Officer are competent, well trained and experienced; it seems like it's a beautiful night and they can handle any minor problems that might arise during the descent and approach. The Captain sees no need to go through all the formalities of the laid-down procedures for briefing for a full IFR approach and go-around.

It takes a brave First Officer to contradict this, because implicitly the F/O would need to deflate the Captain's over-confidence: it is far easier and, for an inexperienced or junior pilot probably more logical, to accept what the Captain's mental model seems to be, which is that all will be well.

This false sense of security is frequently reported as "complacency", "poor airmanship" or "lack of professionalism", and in 2013 a Royal Aeronautical Society safety seminar on pilot monitoring referred to the need for crews to "cultivate a healthy unease" - in other words, always be suspicious, especially if things seem to be going well.