A 2010 "in charge" factor loss-of-control incident ?

During a First Officer's sector into JFK New York in an Airbus A380, the Captain (as PM) repeatedly assisted the First Officer's attempts to retrieve a hopelessly "hot and high" approach. Switching far too late from "assist" mode to "prevent" mode, 1 mile before the threshold the aircraft was at 480 ft and over 200kt.

At this point the Captain finally called for a go-around. The PF, having been concentrating on landing, DID go-around - but in the process, temporarily lost control of the aircraft. The result was the largest and most modern of airliners rocketing through its unusually low designated missed approach altitude, in some of the world's most congested airspace. Flaps were damaged as it reached over 300 kts, as the crew tried to regain control and obtain clearance to maintain a higher altitude.

While monitoring by the Captain as PNF did prevent a catastrophic crash landing or over-run, this can hardly be looked on as a satisfactory outcome. The Captain as PM had repeatedly assisted the First Officer in his continuing an approach which had become dangerous, reconfiguring the aircraft to extend the flaps at high speeds when requested by the First Officer.

For his part, the First Officer as PF had become so fixated on "landing, come what may" that his mental preparation for a go-around, with its low G/A height limit, had been totally overlooked.

It is hardly conceivable that the Captain as PM had actually been quite happy with this approach until suddenly at the last moment, when he called for a go-around. But any corrective influence he had was obviously quite inadequate, even though as aircraft Commander he could have imposed his authority much earlier.

One can imagine this dangerously delayed reaction was at least in part due to reluctance to interfere with the First Officer's conduct of the flight. This reluctance to interfere is what is meant by the "in-charge" factor.

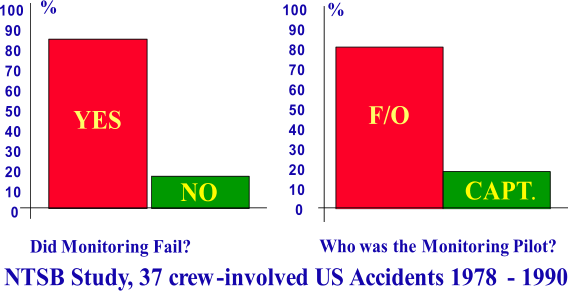

Historic data

The existence of something like this does seem to be confirmed by the NTSB and other US data. In the US environment "cultural" factors in the authority gradient, such as natural deference to authority are probably minimal, and the distribution of flying to F/Os probably comes closest to 50% . While data collected in the NTSB 1994 study (discussed in more depth elsewhere) does not actively prove this theory, it does show that although Captain do have a much higher success rate at monitoring and challenging than F/Os, it is still nowhere near 100%.

More recent data from a study of approach and landing accidcents and incidents 1990-2015 shows that although CRM training may have improved the situation, the Captain was the pilot flying in about 70% of cases.

During a “Captain’s leg”, his authority is composed of both elements - a “rank” element and a “role” (“in charge”) element. During a First Officer’s leg, the F/O has a varying degree (derived from experience and other interpersonal factors) of extra authority, due to his or her “in charge” role - "In Command, but Under Supervision".

During a “Captain’s leg”, his authority is composed of both elements - a “rank” element and a “role” (“in charge”) element. During a First Officer’s leg, the F/O has a varying degree (derived from experience and other interpersonal factors) of extra authority, due to his or her “in charge” role - "In Command, but Under Supervision".

In both cases this implied authority acts as an inhibiting factor on the other pilot’s ability to correct errors, and in some cases can over-ride the "legal" authority gradient that would normally exist between a Captain and a First Officer, as may have been the case with the A380 event just mentioned.

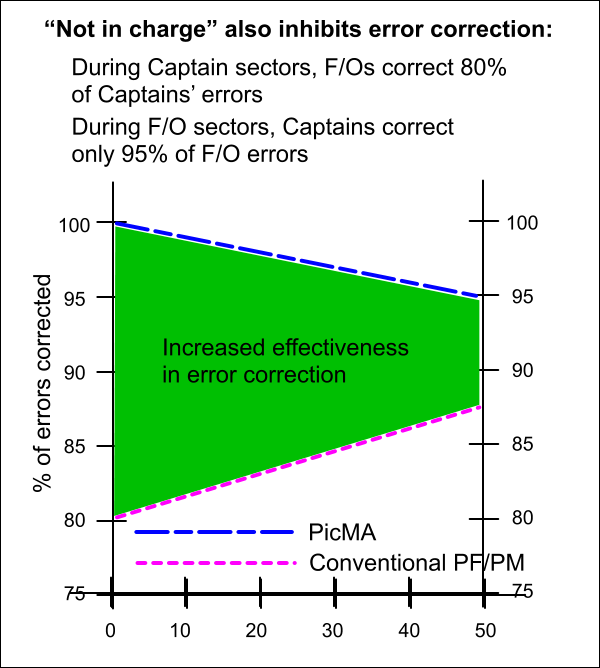

Effect of "in-charge factor" on PicMA benefits.

Assuming that this theory is correct and that the “in charge” element does inhibit correction by a certain amount. Applying it to the diagram seen earlier where we assumed F/Os correct 85% and Captains 100% of errors.

Let’s say that the effect is to change the correction rate by 5% of the errors. In other words, you correct 5% more when you feel you are in charge, and 5% less when you don't. (Once again, please note that these numbers are simply to illustrate the direction of the effect, not the actual magnitude. We know that generally First Officers pick up far more than 85%).

Traditional PF/PM flying.

In the traditional PF/PM operation, the F/O now corrects only 80% of the Captain’s errors during Captains’ sectors and the Captains correct 95% (instead of 100%) of errors during the F/Os’ sectors.

If the Captains fly all 100 sectors, they will make 100 errors, and 80 will be picked up, leaving 20 uncorrected ones. Now, say they “give away” 10 sectors. There will be 90 errors on “their” sectors, of which 80% will be corrected (leaving 18), whilst during the F/Os’ 100 sectors there will be 100 errors, 95 of which will be corrected. Net result: 18.5 uncorrected errors.

If the Captains fly all 100 sectors, they will make 100 errors, and 80 will be picked up, leaving 20 uncorrected ones. Now, say they “give away” 10 sectors. There will be 90 errors on “their” sectors, of which 80% will be corrected (leaving 18), whilst during the F/Os’ 100 sectors there will be 100 errors, 95 of which will be corrected. Net result: 18.5 uncorrected errors.

This will continue until at the point where 50% of the legs are “given away” the uncorrected errors are down to 8.5. The possible range is between 12.5 and 20 uncorrected errors, or the correction rate is between 80% and 87.5%.

"PicMA" flying

Now take the situation where the flying which contains “correctable” errors (i.e. other than the actual takeoff and landing) is delegated using PicMA. The F/Os’ correction rate is increased by the 5% “in-charge role” factor to 90%.

If the Captains “give away” no sectors, all the correctable errors are made by the F/Os, and all are corrected. Net result is as before, zero uncorrected errors. Now assume that the Captains give away 10 sectors. The result will be zero uncorrected errors during the 90 “Captains’ sectors”, and 10 errors made by the Captain during the F/Os’ sectors, of which 90% are corrected. Net result: 1 uncorrected error.

At the 50/50 leg and leg flying level, there will be a total of 5 uncorrected errors, compared with 8.5 during “assisted” flying. The range is between zero and 5 (upper blue line on graph), compared to a range of 20 to 8.5.

What to conclude?

From this demonstration, it's clear that if you believe that the only factor that reduces monitoring effectiveness and error correction is the Captain-First Officer rank difference, there will be a safety benefit from “PicMA” flying, unless the operation has an exact 50-50 leg-and-leg random distribution, because in that case the two systems are equal. But in any more realistic and likely situation, where there is less than 50/50 random allocation of flying, there will be a safety benefit.

However, if you accept that any effect at all can be due to an "I'm not in charge" factor, there will always be a benefit to delegation.

In practice, changing to the PicMA (delegated flying) procedure will always provide a safety benefit, regardless of the airline’s policy in respect of First Officers’ sectors.