The benefits of "advance delegation".

In the section of this site dealing with "culture" in flight operations, there is a reference to an "ethnic theory of plane crashes". In his book "Outliers", Malcolm Gladwell, a well-known but non-expert writer, is writing primarily about national cultures, but interestingly he focuses on an example of a problem arising in flight, described to him by a very experienced airline Captain, Suren Ratwatte.

Gladwell notes that the Captain resolved it very effectively by immediately delegating the PF duties to his First Officer, concentrating on dealing with the complex logistic and communications aspects himself. He then re-assumes control to perform a critical over-weight landing at the diversion airport. In other words, as soon as the problem becomes evident, Capt. Ratwatte departed from the basic "Captain is PF" SOP and adopted the "delegated flying" aspects of the PicMA procedure.

In fact of course this is eminently logical. If delegation provides a better way of managing situations which have become hazardous, isn’t it equally a better way of managing situations to avoid them becoming hazardous? Incorporate delegation into the SOP, and there is no requirement to deviate from the SOPs to achieve good CRM.

Manufacturers such as Boeing now emphasise that monitoring and intervention strategies need to be created and maintained in normal operations, and then carried over to non-normal situations, and using PicMA seems an extremely easy way to achieve this.

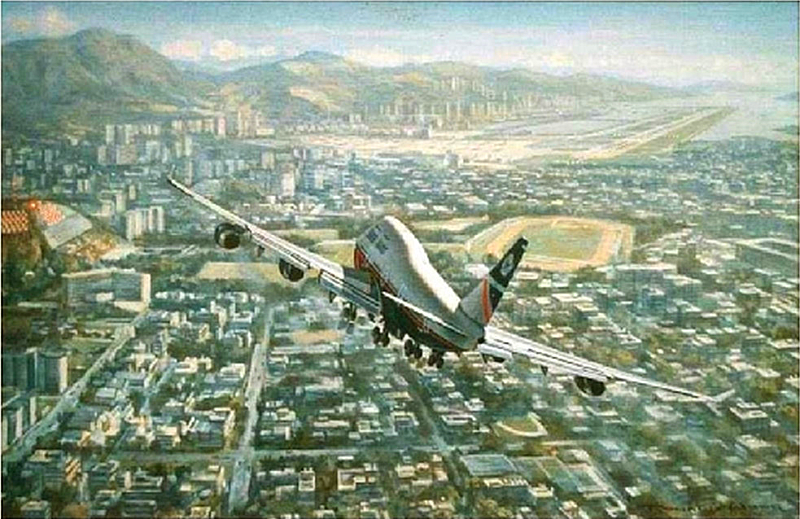

An example of the benefits of having the delegation of flying already in place was observed was on an approach to Hong Kong after a non-stop flight from London in a B747-400. The flight was to the Kai Tak airport, well known for its single short runway, high surrounding terrain and awkward approach to R/W 13, which involved a significant turn of 450, starting at about 400 ft. because of the terrain.

The weather, although not "bad" in normal terms was cloudy and close to the AOM of 700ft/2000m for this approach, which involved an off-centreline ILS, requiring a visual turn of 45 degrees initiated at an altitude of about 400ft a mile from the threshold, to line up with the runway. The painting below by Ronald Wong illustrates this approach in good weather.

The operation was being conducted using the airline's PicMA SOP procedures, so the First Officer was acting as PF during the approach. He was relatively new on type and although he had received the necessary training and briefing, was making his first actual arrival at Hong Kong. After being extensively vectored by radar, under speed restrictions, fuel remaining was approaching the minimum, but a normal landing was anticipated.

The operation was being conducted using the airline's PicMA SOP procedures, so the First Officer was acting as PF during the approach. He was relatively new on type and although he had received the necessary training and briefing, was making his first actual arrival at Hong Kong. After being extensively vectored by radar, under speed restrictions, fuel remaining was approaching the minimum, but a normal landing was anticipated.

Following ATC instructions to reduce speed, the F/O (PF) called for flaps to be selected. However when the Captain (PM) selected the flaps, an EICAS message occurred as one wing's flap motor malfunctioned. The Captain instructed the F/O simply to continue the approach but maintain the current speed, and as PM informed ATC that the aircraft was unable to reduce speed for the moment. The Captain started to action the QRH procedure, and it quickly became apparent that a landing would need a considerably increased Vref.

The Captain's concerns were then that the fuel state did not permit any extensive trouble-shooting, but the higher approach speed would possibly be excessive for the limited runway length available. However, any diversion would generate serious logistical problems, the crew were already at the limit of their allowable duty.

He informed ATC that he would continue the approach, maintaining a higher speed if necessary, down to 1000 ft, at which time he would either commit to a final approach or be requesting an immediate diversion. This R/T exchange obviously informed the F/O of the plan as well, and the Captain continued to work through the QRH, with particular attention to cross-referencing the speeds and landing distance available, using the supernumerary ("heavy crew") pilot to crosscheck the calculations.

Once satisfied that a landing could be completed, he re-stated the landing criteria (speeds and configuration etc) to the F/O, warning that as the low-level turn would be a considerably higher groundspeed than normal the bank angle needed to track the turn would also be higher than usually acceptable, especially at such a low level.

He informed ATC of his intention to continue approach to a landing if possible but at higher speed than usual. This would possibly involve additional braking, and he requested alerting the airport fire services to potential brake overheating issues. He also warned ATC that the flight would be diverting immediately in the event of a go-around.

After completing the QRH items and the appropriate landing checklist items, the Captain was then able to devote most of his attention to acquiring the curved lead-in and approach runway lights, as the aircraft descended through the broken cloudbase, while the F/O continued to fly the off-centre-line ILS to Decision Height.

The curved lead-in lights started to become visible about 200 feet above DH, and the Captain was able to make a relatively relaxed assessment of the visual cues, prior taking control at DH to manoeuvre the aircraft round the final turn to a high speed but otherwise normal landing.

The crew considered the entire episode relatively stress-free, as the Captain was able to make both strategic and tactical decisions without the pressure of having to fly the actual approach on instruments, while the crew were not required to do anything outside their normal duty allocations.