Human limitations.

It'simportant to recognise the limitations pilots have when making an approach by purely visual means, especially when making use of the limited visual reference available after an instrument approach in poor weather conditions. Words such as ’airmanship' are mentioned as though a pilot has some magical quality that enables him to control the aircraft in these circumstances.

This is probably because almost everyone has experience of visual control in azimuth in poor conditions from every-day life, e.g. driving a car, and assumes controlling an aircraft in two axes (azimuth plus pitch) is no more difficult.

Unfortunately of course this is not true: and it is pitch control which largely determines the safety of an approach. Scientific analysis shows that the control of an aircraft by visual reference is an extremely complex task requiring extremely fine judgement of small changes of the limited information available. A detailed study of the problem can lead one to think that the task is beyond the capabilities of the average human.

Fortunately, pilots approach the problem in their traditionally practical manner and just get on with the job to the best of their ability. The issues involved have been extensively examined in research by several organisations as far back as the 1960s, notably the UK Royal Aircraft Establishment Blind Landing Experimental Unit (BLEU), the NASA Ames Human Factors laboratory team, and the US Air Force Instrument Pilot Instructors School. Similar work was also done in France. These all established the same fundamentals about pilot visual assessments. (The links provide some background on this work.)

Minimum visual information for control.

For the pilot to adequately ‘close the loop’ and provide proper control over the aircraft during an approach, he or she requires the following information from the visual aids:

- current position, i.e. aircraft displacement relative to centreline and glide-slope, and distance to go to the threshold

- flight path, i.e. instantaneous direction of travel or trajectory.

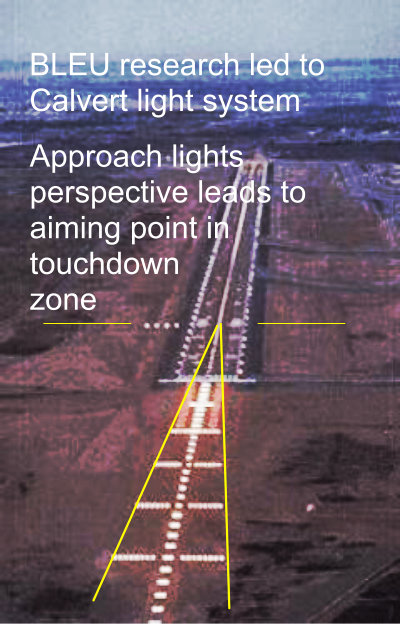

The "current position" can be satisfied by observing the shape of what is available of the visual aids and runway markings, using their perspective image. The layout of the visual aids can make a significant difference to this. The next image shows a runway and Calvert 5 bar approach lighting system.

The crossbars are so arranged that their outer edges are contained by two straight lines which intersect at the aiming point. The significance of this is that the perspective angle of the lights will remain constant so long as the aircraft maintains an approach path which will take it to the aiming point, although it is doubtful that the human eye is capable of detecting subtle changes of this angle.

However, the apparent angle between the centreline and the crossbars is very sensitive to lateral position, and the Calvert pattern provides excellent azimuth guidance. Other approach light systems provide good azimuth guidance but less vertical path information as they do not "point to" the desired approach aiming point in the same way.

The decision-making process is affected by the pilot's overall workload. As might be expected, a pilot who is simultaneously flying the aircraft takes measurably longer to make an assessment and reach a decision than one who can devote his attention to the developing visual cues.